Room 208 in the Crescent Building on Zijingang campus is no less than a museum for miniatures of Chinese timber structure, whose birth-givers are the sophomores of architecture, and the midwife, Prof. ZHANG Yuyu of the College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Zhejiang University.

Lecturing on the History of Ancient Chinese Architecture since 2005, Prof. ZHANG keeps collecting the models made by students as their term assignment. Though her spacious office seems a bit crowded with these scaled-down pavilions and chambers, she still holds the history on textbooks insufficient. “Traditional Chinese architecture exists not only in books, but also in our living experience, ” she says.

A memory to be retrieved

The traditional architecture in China never fails to impress any westerner. “Those engineers who traveled to China in the late Qing dynasty would amaze at the delicacy, the symmetry, and the harmony of our timber structure, while we natives seemed rather indifferent.” Prof. Zhang regrets that the invaluable assets of Chinese architecture had been ignored and scattered among various documents until LIANG Sicheng, an internationally renowned architect, finished A History of Chinese Architecture in 1944 as the first systematic endeavor.

Despite the growing attention drawn to them, these aging wooden buildings are weathered, rotted, and replaced with steel and reinforced concrete that symbolize modernization. “As architects, we should retrieve, understand, and preserve these timber structures as a memory, an identity, and an inspiration,” Prof. Zhang looks determined.

The vitality of traditional architecture is what Prof. Zhang sees through history and reality. “Some Japanese architects managed to transplant conventional ideas into modern constructions, and hence established a global reputation. By contrast, such masters in China are very few, and we still have a long way to go.” That is where Prof. Zhang positions her course: to stimulate innovation based on a thorough comprehension of the history of traditional Chinese architecture.

Observe, understand, and practice

Prof. Zhang disagrees with the majority who interprets her lectures as mere theories to be acquired through reading. Instead, she insists on adding a practice section to the syllabus, which requires every student to craft his or her own model.

This distinguishes her class from any other course of architecture history. . “Only a few schools afford such opportunity for practice, and their assignments are either to submit a design to be materialized by professional craftsmen, or to assemble parts of a structure, say, a mortise and tenon joint,” noted Prof. zhang. But she makes a bold leap by asking students to build a miniature from scratch. “In my opinion, all delicate pavilions, solemn palaces, and splendid halls are produced after rounds of selection, combination, and multiplication of these some modular basic constructive units.”

Modular basic constructive units: bracket

Questioned about the necessity of it, Prof. Zhang is confident to justify her arrangement. “When working on my doctoral dissertation, I traveled four times to a construction site. Only by standing there observing in person, can one attain a full understanding of how a house is erected.”

Such practice proves worthy. While working on their assignments, her students come to understand that timber structures are “alive”. Each choice concerning the material and the cutting method will make a huge difference. “Traditional Chinese construction pertains more to experience than precise calculation, that’s why I keep all the models, some as paradigms and others as lessons, for the coming students.”

Beyond knowledge

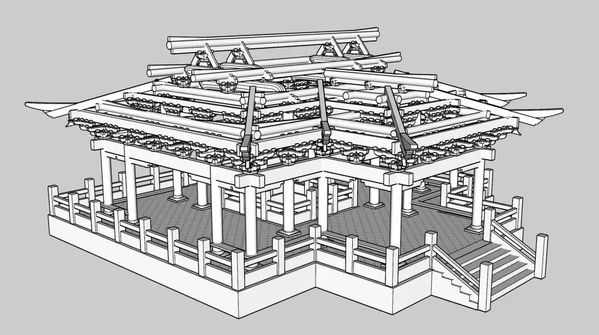

The assignment takes about two months, during which the students choose their buildings, analyze blueprints, order raw materials, and process and assemble them. Each project, though no bigger than a basketball, contains up to 700 pieces of components, posing a daunting challenge to one’s patience and spatial imagination. To help the students fulfill their tasks, Prof. Zhang takes them to a traditional garden in Suzhou for field study, and encourages them to resort to technical assistance such as 3D-modelling.

The sketch up model of the pavilion

“Concentration, dedication, and strive for perfection are the connotations of craftsmanship I’ve learned from this class,” remarks LU Jiaming, a student of the course. “It is also what guarantees the enduring charm of traditional Chinese architecture. And I will carry such craftsmanship on to my future career.”